Revocation for non-use? – FOHLENELF

The case: ‘Fohlenelf’ [foals team] is the nickname of the well-known German football club Borussia Mönchengladbach. It dates back to the time of legendary coach Hennes Weisweiler in the 1970s. That was an era of young players, known as ‘foals’, and fast, attractive attacking play. Many people will recognise the names of these ‘foals’: Günter Netzer, Berti Vogts, Jupp Heynckes, Ewald Lienen, Wolfgang Kleff, Herbert Wimmer, Herbert Laumen and so on.

The club has protected the term as a trade mark for a variety of goods and services, including as a European Union trade mark in 2013.

Borussia also runs a ‘foals shop’ and publishes a ‘foals newsletter’.

David Neng also uses the term ‘foals’. His company offers trips for fans of the club, merchandise, drinks and tickets. For ‘FohlenFans’ [foals fans], he also sells spirits under the German brand

![]()

[foals gulp]

[foals gulp]

In 2019, he filed an application for the revocation of the ‘Fohlenelf’ trade mark, based on non-use.

An EU trade mark must be put to genuine use in the European Union within five years of its registration in order that it does not lapse. Even after that, any qualifying use must not be interrupted for an uninterrupted period of five years, to ensure the trade mark is not at risk of cancellation. The protection of a trade mark is reserved exclusively for commercial exploitation that has to be significant in quantitative terms. This use covers four aspects: place, time, extent and nature of use. Genuine use must cover all these aspects to a sufficient extent.

Borussia’s trade mark had been registered for more than five years. Therefore it had to have been put to genuine use in the five years prior to Neng’s application for revocation. Borussia had to prove this use in order to prevent its trade mark from being cancelled.

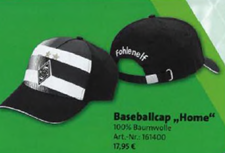

The club first submitted catalogues from the relevant period. They contained a number of merchandise items on which the trade mark was depicted together with the item number and price, such as the following cap:

However, some of the merchandise only featured the Borussia logo, not the brand name:

Use of the trade mark on these particular items could not therefore be proved via the catalogues.

While Borussia did not provide any evidence of nationwide distribution, this did not count against it. After all, it is well known that an element of the business of big football clubs is merchandise. This usually makes a not inconsiderable contribution to their income. Since it was also possible to provide a number of invoices, the overall picture suggested that the core range of catalogues bearing the brand was indeed sold in sufficient quantities.

For the registered ‘mineral and aerated waters and other non-alcoholic beverages’, Borussia could only prove the distribution of a limited edition of 100,000 ‘Cola Zero’ cans bearing the ‘Fohlenelf’ brand. However, this was not enough. A limited edition is by its nature short-lived and temporary. It was insufficient to maintain or gain market share for the registered goods in the beverage industry. It therefore could not be considered significant enough.

Borussia also sold beer from the Bolten brewery in a party keg, which was labelled ‘Älteste Fohlenelf der Welt’ [Oldest foals team in the world]. But did this constitute a use of the ‘Fohlenelf’ [foals team] trade mark? The way the slogan was worded implied an alternative meaning: ‘the oldest of several foals teams in the world’. This was completely different from the standalone ‘Fohlenelf’ name. Therefore, the use of the ‘Fohlenelf’ trade mark for beer was not proven.

To prove the use of the registered trade mark for ‘cosmetics’ and ‘soaps’, Borussia’s only submitted evidence was by way of sales of hair and body shampoos bearing the mark ‘Fohlenelf’. However, the category of ‘cosmetics’ is a very broad generic category of goods. When consumers look for hair and body shampoos, they want to buy a product that performs a cleansing function for the body and hair. Such products may include shampoos in general and soaps. This is why the mark was used only for those products and not for the broad category of ‘cosmetics’.

Borussia’s trade mark was also registered for merchandising services. However, this is a service which is offered to third parties and for which they also pay. Borussia had only sold its own goods under the trade mark in the context of merchandising. There was no use of the trade mark for merchandising.

The same applied to the registered services of advertising and sponsoring. Advertising and sponsoring are also services for third parties and not for the trade mark proprietor itself.

All the goods and services for which genuine use had not been proved were subsequently deleted from the list of goods for the mark ‘Fohlenelf’. However, the mark was retained for the element of the goods and services for which genuine use could be proven.

General Court of the European Union of 7 December 2022, T-747/21.

Learnings: The case is a lesson to anyone wishing to maintain the validity of their trade mark. Logistics should be put in place to enable the trade mark owner to prove at any time that commercial use of their mark is significant in quantitative terms for each of the registered goods or services by place, time, extent and nature of use. It should be borne in mind that, in the case of broad generic terms, genuine use must be shown for each coherent sub-category whose goods or services have the same purpose and intended use and fall under the generic term. In addition, the mark must actually appear on the goods; and services must actually be provided to third parties under the mark.

Reference: Please also read the article: